Jesus turned toward Jerusalem. On the way, He told His disciples He would be taken captive and handed to the Roman government for trial. They knew Him well and were devoted to Him, but what happened to the leader could well be the fate of His followers. That He admitted He would be captured seemed a confession of defeat. His disciples were afraid, and they wished themselves elsewhere.

The reason Jesus decided to make a triumphal entry into Jerusalem was because of His impending capture. He believed in His mission, and His disciples believed in Him: that He was God’s appointed messiah. He would give His disciples something to remember in the lonely days that lay ahead, something dramatic which they could look back on, and on which they could feast their minds with remembrance. He would make a public declaration of His messiahship, ride into the holy city as God’s Chosen One, in the traditional fashion, and He would allow the people to acclaim Him. He would give His disciples one bold moment to infuse courage into their fears.

If we were to follow the same route as Jesus, we would take the turn of the path around the hill, and great Mosque towers would suddenly rise before us; beside the towers would be the vast enclosures of the Musselman sanctuary; beyond this imposing center the city would stretch out of sight. When Jesus took that turn, the magnificent, sprawling city lay before Him, as magnificent in the first century as today. The temple was in the center, surrounded by gardens, and beyond, as far as the eye could see, were the homes of the people. The valley of Kedron met the valley of Hinnon, and Jerusalem rose from the abyss.

Jesus rode beyond the turn of the road, and the great metropolis lay before Him, the city He had loved and which was so full of history, sin, and glory. He wept. “If thou hadst known,” He said, “even thou, at least in this thy day, the things that belong to thy peace! But they are hid from thine eyes.” Jesus entered the city with triumph, but He may not have made the stir we sometimes imagine. Though of significance for us, when one thinks of the size of the city and the number of the inhabitants, it was probably a thing done in a corner. Hundreds of men, many of them fanatics, only some of them worthy, every year claimed to be prophets. As the various disciples acclaimed their leaders, the crowd, with good humor, would join in the excitement. When Jesus entered and His disciples cried, “Hosanna to the son of David! Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord!” — the people who were in a carnival mood would take up the cry until hundreds and perhaps thousands joined the procession; but their sentiment was of good humor rather than of agreement.

The meaning of the triumphal entry was greater to the disciples who worshipped their Lord and to the evangelist who told the story than to the casual wayfarer. To us who live a long time after the event and who know what Jesus has meant in our lives and what He has meant to our civilization for two thousand years, the triumphal entry means He truly was the son of God, the savior of the world sent to announce salvation. If it be true that it was only a single, bold moment, a flash of light in a sea of tragedy, a bright flame quickly snuffed, a beautiful, delicate growth soon to be crushed by the authorities, we believe that the flame which men put out may yet be the flame to which we must repair and that the announcement made that day was by the Son of God, a divine proclamation by One who may and must conquer the world.

I saw the Conquerors riding by With trampling feet of horse and men Empire on empire like the tide Flooded the world and ebbed again. A thousand banners caught the sun, And cities smoked along the plain, And laden down with silk and gold And heaped-up spillage groaned the wain. I saw the Conquerors riding by, Splashing through loathsome floods of war — The Crescent leaning o’er its hosts, And the barbaric scimitar — And continents of moving spears, And storms of arrows in the sky, And all the instruments sought out By cunning men that men may die! I saw the Conquerors riding by With cruel lips and faces wan: Musing on kingdoms sacked and burned There rode the Mongol Genghis Khan; And Alexander, like a god, Who sought to weld the world in one; And Caesar with his laurel wreath; And like a thing from Hell, the Hun; And leading, like a star, the van, Heedless of upstretched arm and groan, Inscrutable Napoleon went, Dreaming of empire, and alone. . . . Then all they perished from the earth As fleeing shadows from a glass, And, conquering down the centuries, Came Christ, the Swordless, on an ass! Harry Kemp The Conquerors

For all that the triumphal entry was done in a corner, Jesus did gain popularity, and this caused the displeasure of the religious leaders. “You are too popular,” they said. “Silence the crowd and return to oblivion.” “I tell you,” Jesus replied, “if these people are silent, the very stones would cry out.” This was an interesting figure of speech: the very stones would cry out. Why did He not say: “The trees will talk,” or “The ass will speak”? A tree has life, which a stone does not. An animal can move, which a stone does not. A stone lies inert. If it falls, it cannot move of itself but must first be moved by something outside of itself. Though it is true there is a romance to the history of stones and geologists tell us exciting stories about their age and composition, they perform a humble service. A stone is one of the least forms of matter. On the other hand, stones have sung — even as Jesus said they would.

We measure our civilization in no small part by the temples that are built of stone, and the greatest testaments of our culture are monuments erected in the name of Jesus. I wonder if we still build them. We build many churches. But do we want the cross of Christ to be higher than the tallest building? I wonder if the picture of a perfect city is that of a church, its spire pointing to the heavens, surrounded by neat cottages — or an ugly megalopolis. When a young man in Melbourne, Australia, I recall one of the elders of our brotherhood standing in a public meeting to say “I want the cross of Christ on our church to stand higher than the roof of the Melbourne Hospital.” He was not speaking of literal height, as the Melbourne Hospital was many stories high, but he was using a rhetorical expression to indicate what he believed to be most important. If our song is not of Him, time will ensure that there will be no song.

The Scriptures speak of God Himself as a stone. “The Lord is my rock, and my fortress, and my deliverer, my God, my rock, in whom I take refuge.” Jesus referred to Himself as a stone: “Behold, I am laying in Zion a stone that will make men stumble, a rock that will make them fall.” When the apostle Peter, whose name means a stone, called Jesus the living stone of our faith, he said that the followers of Jesus were also to be living stones: “Come to him, that living stone, rejected by men, but in God’s sight chosen and precious; and like living stones by yourself built into a spiritual house.”

In the year 1827, in a small fishing village of Japan, a little waif was born whose name was Manjiro. One of his greatest loves, as he grew into a teen-age boy, was to go fishing; but one day his boat was blown out to sea and he was stranded for six months on a deserted island. He became emaciated. Sailors from an American whaling boat eventually found him and took him home with them to New London, Connecticut. Wanting to make his living in the same way as his guardians, young Manjiro studied mathematics, astronomy, and navigation. The years passed slowly, but a great day came when he had his own ship. He returned to the waters where he was found many years earlier, and he went beyond those waters into the harbors of Japan — at the peril of his life. Japan was isolated from the world, and chance callers were often killed. But Manjiro felt a mission to be a singing stone to tell his people of a good world beyond their shores of which they need not be afraid. Largely due to Manjiro, the doors of Japan were opened. He could have lived in America. He need not have endangered his life by entering the Japanese port. He could have lain inert, doing nothing, content with making a living. He became a singing stone.

The apostle Peter was a rock who learned to sing, but it took time. He was an uncouth fisherman when Jesus called him. Loud of talk and big of heart, he seemed to change in the presence of the Lord; but his change was more apparent than real. His behavior was from the inspiration and the guidance of the Master rather than from inward character. He failed at the first temptation. When the crisis came and Jesus was captured, Peter denied his Lord. In the third denial, his vehemence was so strong and his language so crude and vulgar that even the soldiers were shocked. He was not yet a singing stone but one of those inert pebbles that are bounced by the current, incapable of inward direction.

But the life of Peter did not end with denial, and he became a singing stone. He saw Jesus after the crucifixion. For each time Peter had denied Him, Jesus gave three pledges of love. Three times Jesus asked him “Simon Peter, lovest thou me. . . . Lovest thou me. . . . Lovest thou me?” Three times came the answer: “Feed my lambs. . . . Feed my sheep. . . . Feed my sheep.” Peter’s heart was broken, and because of the admittance of shame, he became the rock of history. The sinner became the saint, the saint became the witness: a pillar of strength to the brethren and the apostle of the ages.

Something like this is meant by Palm Sunday and the statement of Jesus: “Silence these people and the very stones will cry out.” We are to be singing stones.

Editorial

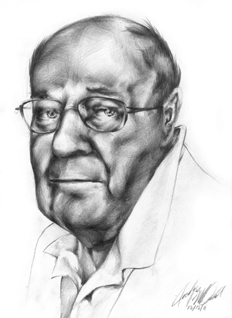

My dad, Angus MacDonald, founder of The St. Croix Review 45 years ago, died on December 4th. He was 88 years old and had lived an energetic and purposeful life. He was an Australian immigrant who loved America because after WW II America was large, and there was freedom here. America offered him the education he hungered for.

Most of us don't write an autobiography, and readers of The St. Croix Review are lucky that Angus did (A Straight Line) because his story not only sketches his extraordinary character but also reflects America, the wide-open nation where a person of ambition and courage could claim a bright future through hard work. America after WW II and the Great Depression did offer unlimited potential, and Angus traveled far down a career path, being a minister in a Congregational Church, but eventually, his youthful idealism encountered bitter opposition in the form of bureaucratic power structures. He became discouraged with the ministry after 25 years and left the church to found The St. Croix Review, which he made the focus of his life's work.

Angus was "honest as the day" (one of his habitual phrases), he searched for a religious faith that was intellectually honest (a life-long pursuit), and he was a rebel against the ignorant and dishonest, power-driven lust for control that he found first in a labor union in Australia, in church hierarchies, and finally in the burgeoning multitudes of politicians at all levels who are willing to say and do anything so that they could wield power.

Dad was fiercely independent, and he hated dishonesty in powerful people; it became his life's work to fight back, as he saw how government control stunts and ruins peoples' lives. Under cover of rhetoric about uplifting and educating the poor he saw clearly how the politician's main interest is in reelection, and the acquisition and maintenance of authority - any good politicians do is accidental, a happy coincidence.

It is ironic that my dad was a much better rebel than any of the 1960s hippies whom he opposed; the hippies who fought "the establishment" are now clamoring for government healthcare and pensions. Today the wrinkled hippies are yearning to be wards of the state. My dad never stopped fighting - when he read articles on politics at his desk up to the end of his life he scowled at the arrogance and foolishness of politicians.

Angus got a good portion of his moral fiber from his father. Angus was born on November 24, 1923, in Melbourne, Australia, to Herbert George and Dorothy May MacDonald. He was the youngest of three children. Angus' father began work at age 14 in a piano factory. In his early 20s Herbert courted Dorothy by riding into town on a draft horse; they married at age 23. Herbert worked on the family farm for a time but left home because his father, Duncan, took all his money. Herbert opened a fruit and greengrocer's shop, getting up between 2 and 3 a.m. and working all day, but he tired of the hours.

Herbert bought a truck and went into the trucking business - his new venture coincided with the onset of the Great Depression, and everyone in Australia was hard hit. The drivers would line up "one behind the other" in the hopes of finding work. After years of effort the business grew and Herbert could buy additional trucks. Angus, in his autobiography, A Straight Line, writes of his father:

He bought the chassis and engine, and that was all. Cabs were silly, he thought. When you made a delivery, you had to climb out of the cab, walk to the back, and climb onto the tray to get your merchandise. The sensible thing was to build an open van and walk from the driver's seat into the back seat. He never liked those crude bodies with square fronts, so he curved his from the top of the body down to the windshield. His were the only ones of their kind in the city of Melbourne.

The business Herbert started in Australia during the depression is ongoing, with Herbert's grandchildren continuing a prospering operation. Angus' brother Donald continued the business after Herbert; Angus chose not to be a trucker.

The MacDonald family was poor during the depression though they did not know it, as everyone was poor. They had no butter, ham, chicken, turkey, or corn (corn was pig's food). Angus' first bicycle was held together by hose clamps. One of the games Angus played was "cherry bobs" - they dug a hole and flipped cherry stones in. Angus was a reckless, boisterous lad, breaking his arm one day, breaking his nose another, and skinning his nose later. He must have drawn attention to himself, as his English teacher asked him to behave, saying "Angus, if you misbehave so will the whole class." She set him up front, prompting him to be a good example - it worked! Although outside English class Angus apparently needed additional attention. The principal set him the task of writing the school slogan "hundreds, perhaps even a few thousand times": "If all the school were just like me, what kind of school would this school be?" Angus had to walk between three to four miles to school. Despite having epilepsy as a child he did develop into a very good long-distance runner, becoming a top runner of his school and club.

After graduating from high school Angus worked in factories. At the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation his first job was to hand out requisition numbers to workers for spare parts. Not far into the first morning he was visited by a union representative who told him he made the job look too easy. He was told to slow down; this was his first brush with union methodology. Angus quit on the spot and was transferred to the mailroom, later to the engine factory, and then to labor costing of aircraft frames - he was placed in charge of the department. But his heart wasn't into factory work.

His heart was in the church that

. . . has been a large part of my life from as early as I can remember, and I was a simple little boy who accepted the ideals that were presented to us. For some reason or another, I was called "the little minister" when I was only eight years old. . . . The church and its fellowship gave us what intellectual stimulation we received. The school gave us learning but not idealism and inspiration. I was asked to give a sermon when I was about eleven and was comfortable doing so. . . . I did have the ability to bring separate things together. I guess I was always preachy and always an arguer, and I suppose I was always conservative, not in ideology but in temperament.

Leaving factories behind he enrolled in the College of the Bible to become a clergyman, a decision that angered his father:

No one in the world was more honest than my father, but he would never go to church because he did not believe the nonsense handed out. He did not approve of my becoming one of that "starving bunch of hypocrites."

The respect Angus had for his father gave bite to his father's words, "starving bunch of hypocrites," that compelled Angus to seek solid substance for his faith, to seek intellectual respectability. Angus was not to be satisfied with rote theology.

The College of the Bible was small by America's standards with fifty students and three or four faculty. But the studies were worthy: church history, ancient history, Greek, New Testament, Old Testament, comparative religion, pastoral theology (how to behave with your congregation), and the art of preaching. Angus acquired a thirst for learning. He had to be convinced that a position or an argument was true. In New Testament class he asked Mr. Pittman why "we" had to believe Christ rose from the dead:

Little Mr. Pittman went red in the face and said, St. Paul hath said, "If Christ did not rise from the dead, then our faith is in vain." That did not impress me as a valid reply. I wasn't asking for a quotation but a reason for belief in immortality. Later on, in "secular studies," I found some answers one could legitimately accept. Mr. Pittman was so upset by my question that, in other classes, he lost his temper about some of the young students who did not believe the faith.

Angus was given a student pastorate at Kyneton Church of Christ sixty miles out of Melbourne that could hold sixty people. There were two services every Sunday, and Sunday school in the afternoon. Judging by my knowledge of his views, and the numbers of words devoted to her in A Straight Line, my dad was more deeply inspired in his faith by the organist of the tiny church than by his theology teachers:

Jessie Goudie was our organist, a single woman probably in her late fifties, tall, thin, her long grey hair tied in a bun at the back of her head; she sang with a loud voice to accompany her playing. She was great on the "steps of salvation," and she sang loud and clear with the hope that some sinner might hear and be saved. The steps of salvation were hearing the word of God, repenting of your sins, confessing them, being baptized, and rising to walk in the newness of life. We smile improperly at the mechanical simplicity because what Miss Goudie believed and was conventional belief in our churches was as sound as anything could be - and the mechanical simplicity was of help to those in trouble.

Upon graduation from the College of the Bible a kind principal, E. Lyall Williams, wished him well and said: "You believe in Jesus of Nazareth don't you? See how far you can go from there."

On May 12, 1946, Angus boarded the S.S. Marine Lynx, the first civilian crossing from Australia to the U.S. after WW II. He came to America for an advanced education. There were no comforts on the ship and the passengers amused themselves by giving lectures to each other. Angus talked for forty-five minutes on the need of religion for a philosophical basis.

Angus spent a couple years at Butler University, Indianapolis, to adjust his Australian degree to U.S. standards. He paid his own way by loading apples in a store, working at Butler's kitchen, and as an assistant pastor. His sparse meals were capped by suppers of "a small container of milk and half a packet of raisins" - he ate in the cemetery as it was "delightful in warm weather."

Angus had a choice: he could take a Ph.D. in philosophy of religion at Chicago Theological Seminary, or he could go for a Ph.D. in philosophy at Columbia University in New York - he chose Columbia and philosophy. Years later he encountered a professor from Chicago Theological Seminary who spent several hours trying to convince him that religion had nothing to do with behavior or morality.

Angus' description of his professors and his courses at Columbia, and of his time as a pastor in various churches in the area are the most lovingly told sections of A Straight Line. He began a life-long love of music. He sang in choir while at Butler, and in New York he came across first-rate musicians and composers. At this stage he learned to play the piano, a habit he was to exercise until the last years of his life. I have memories of him playing Shubert, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, etc. for an hour after lunch everyday while I was working for The St. Croix Review twenty years ago. He also took up golf during this period; in Stillwater, across the street and up a hill from his home and office is Stillwater Country Club, where he played golf many afternoons for four decades.

At Columbia he studied the history of political philosophy, post-Aristotelian philosophy to Plotinus, the history of British empiricism, nineteenth century idealism, modern philosophy, the philosophy of St. Thomas, etc.

Here is my dad at his height of enthusiasm:

Ernest Nagel amused me. He taught mathematical logic and argued that logic was deductive. To prove the point he wrote theorems on the board and deduced marvelous conclusions. I visited him in his office and claimed that the deductions were from dogmatically asserted inductions and that made his basic argument false. Logic was just as much induction as deduction. That was obvious as the nose on one's face, it seemed to me then and seems to me now, but he wouldn't admit it.

Here is my dad at his most idealistic:

It dawned on me after a while that these learned men to a man . . . knew the history of intellectual thought as well as the palms of their hands, and had long since come to their particular, and various, points of view. There was no reason having an argument about anything, and besides, at their level of sophistication, the only way argument could be advanced was through the printed word. They met, not to disagree, but to explore with sympathy even the most absurd kind of human behavior. This was a lesson in tolerance I hope never to forget.

Angus relates that Columbia professors of this time never taught using their own books, and never shared what their own beliefs were, the focus always being on what a historically prominent intellectual, such as St. Thomas Aquinas, believed. Angus never knew what his professors themselves believed! The contrast with today's completely politicized universities could not be starker.

Angus first met opposition as an assistant in the Methodist church. A pastor he knew applied to the bishop for permission to go to a conference on alcoholism - permission denied.

I began the quarrel with authority that was to be a mark of my life. . . . I was beginning to learn that, in a controlled church, or any other controlled organization, one does what he is told rather than what he believes.

There were annual meetings of the Methodist conference in New York; attendance was "compulsory - among grown men." He heard stories about disobedient pastors who were sent to pastorates that paid a pittance. He knew servile pastors. Once he was told to give a sermon prepared by the central office; it was decided that all the clergymen would present the same sermon. He refused, and his disobedience was noticed. Angus' mother and father visited from Australia and he needed an extra week off. The district superintendent had waited some time to retaliate. He said: "We had a man like you in Long Island. . . . We took care of him and we'll take care of you."

The next day Angus went to New York to inquire about becoming a Congregational minister. There were no canned sermons in the Congregational Church; attendance at conferences was not compulsory. Angus could be a "lone wolf," and he could work out his faith as best he could. In the Congregational Church there were no politics and no fear of where the bishop might send him, or so it seemed at the time.

Upon the completion of his studies he became an assistant pastor at two different churches in Toledo, Ohio. These were happy years, during which he got married to his lovely wife Rema, to whom he would remain married for fifty-five years, having three children: Barry, Gregor, and Beth. Angus enjoyed starting single's groups and taking part in the choir.

It was during his time in Ohio that Angus encountered jealousy from a more senior minster, but a far more troublesome development began in the Congregational Church: there was a movement to merge Congregational churches with the Evangelical and Reformed Church to form the United Church of Christ. The move was an attempt to create the same type of power-driven hierarchy as the Methodist Church. Angus took part in a suit against the merger. The resulting conflict began years of stress. Writing of a national meeting Angus wrote:

Those who tried to speak were hooted at with sneering comments made about them. It came to the place where I could not associate with ministers of the opposing point of view because the animosity and characterization of us as radicals was so violent that I became ill.

There was also a drive among church hierarchy to make politics a prominent feature of church doctrine:

The Christian faith had long since been forgot, for the interest of the day was in politics, where it remains. I had no objection to social action, for I agreed that the church without applications to social life was incomplete, but I was not a left-wing radical as they were, arguing for socialism, pacifism, bringing down of governments, taking side in issues that could be variously interpreted. . . . My objection was their demand that the denomination speak with one voice rather than the voices of thousands of churches that were not of the same mind. I was for liberty; they were for totalitarianism.

Angus lost faith not only in Church "officials," who wanted power, but also in the majority of the clergy. Leaving Ohio he took pastorates in Hutchinson, Kansas, and lastly in Bayport, Minnesota. The sermons he has left us are of high intellectual caliber. They mix history, philosophy, economics, ethics, and bedrock Christian values. They are timeless and well worth republishing from time to time, as I will do.

Angus decided to leave the church, and 45 years ago he founded theSt. Croix Review. William Rickenbacker, who was a regular author for The National Review, wrote an introductory ad in National Review in 1967 that got Angus off on the right foot. The first issue was published on January 3, 1968, with 500 some subscribers. Angus' aim was to publish the most intelligent and better-educated people in the United States:

I never ask their sex or race or religion or background. If they say something sensible and simple that is constructive I shall publish them.

Angus made friends with some of the leading conservative thinkers of the time through his membership in the Philadelphia Society, and they became his authors. These writers include William Rickenbacker, Russell Kirk, Yale Brozen, and Milton Friedman.

Angus was recklessly courageous and blissfully ignorant of the task ahead of him in the difficulty of publishing a journal, national in scope, from the Midwest. How does one earn prominence with a small budget? (Still a problem today.) Survival is an astounding accomplishment. There were no computers in 1968. Subscriptions were managed on index cards, sorted and tracked in monthly files. Each label on each billing card individually typed - imagine the time consumed with menial tasks.

Characteristically bold, Angus decided that he would cut costs by printing the Review himself, so he bought a printing press, even though he knew not the first thing about printing. Angus printed the next issue - another astounding accomplishment. Up to fifteen years ago my father and I continued to print the Review ourselves taking three weeks in the process. Looking back I don't know how we did it, and I cannot imagine those early days with the operation run through index cards. (How were the typesetting, proof reading, and editing squeezed in?) I know now that printing is a craft best learned within the company of more experienced printers, and without knowing experience the novice is often left befuddled - and my dad and I often were. Thankfully now we leave most of our printing to Mike Swisher (who wrote the following essay) and Bayport Printing.

I remember when I was 14 my dad coming upstairs to show me some printing he had done, proudly saying: "No one can do better than that!"

Then there was the time in the 1970s that the IRS tried to put us out of business by taking away our nonprofit status. A powerful person who has remained anonymous made a complaint against us. Minnesota State Governor Al Quie came to our defense and, as best I remember, the Heritage Foundation came to our aid by finding us legal aid.

Angus MacDonald embodied the best American ideal: the rugged individual of strong faith. What he founded continues, into the third generation, with my daughter Jocelyn's pencil drawings adorning our covers.

The amount of influence my father had on America is beyond knowing. Walter Cronkite, as famous as he was, is unknown to our young generation. My father touched people who touched people, who touched people like ripples . . . as do we all. I am working in two rooms full of books, and in each book there are marking that my father left behind. *

We would like to thank the following people for their generous support of this journal (from 11/16/2011 to 1/13/2012): Mary Ellen Alt, Larry G. Anderson, The Andersen Foundation, George E. Andrews, William D. Andrews, William A. Barr, Margaret Barrett, Henry Bass, Alexis I. Dup Bayard, Bud & Carol Belz, Charles L. Blilie, Lind Boyles, Gary & Sue Bressler, Mary & Fred Budworth, Price B. Burgess, Terry Cahill, Dino Casali, John B. Charlton, Laurence Christenson, Thomas J. Ciotola, John D'Aloia, Peter R. De Marco, Francis P. Destefano, Jeanne L. Dipaola, Alive DiVittorio, Robert M. Ducey, Paul Warren Dynis, Ellen & Brian Feeney, Joseph C. Firey, Robert C. Gerken, Gary D. Gillespie, Richard P. Grossman, Judith E. Haglund, Robert L. Hale, Violet H. Hall, James E. Hartman, David L. & Mary L. Hauser, Paul J. Hauser. John H. Hearding, Bernhard Heersink, Quentin O. Heimerman, Norman D. Howard, Thomas E. Humphreys, David Ihle, James R. Johnson, Louise Hinrichsen Jones, Margaret Kelly, Joseph D. Kluchinsky, Gloria Knoblauch, Ralph Kramer, Robert M. Kubow, John S. Kundrat, Alan H. Lee, Don & Gayle Lobitz, Gregor MacDonald, Paul T. Manrodt, Thomas J. McGreevy, Karen McNeil, Roberta R. McQuade, Edwin Meese, Albert D. & Norma J. Miller, Donald J. Miske, Robert L. Morris, Richard S. Mulligan, Ray D. Nelson, Lester C. O'Quinn, King Odell, John A. Paller, Frank Palumbo, Frederick D. Pfau, Gary J. Pressley, Richard O. Ranheim, Seppo Rapo, David P. Renkert, Kathryn Hubbard Rominski, Joseph Schrandt, John A. Schulte, Irene L. Schultz, Harry Richard Schumache, Alvan I. Shane, Dave Smith, Elsbeth G. Smith, Thomas E. Snee, Thomas S. Steele, Frank T. Street, Susan & Ron Stow, Dennis J. Sullivan, Michael S. Swisher, W. G. Thompson, Paul B. Thompson, Elizabeth E. Torrance, Thomas Warth, Alan Rufus Waters, Donald E. Westling, Gaylord T. Willett, Robert F. Williams, Max L. Williamson, Lee Wishing, Piers Woodriff, W. Raymond Worman, Michiko Yoshizumi, David W. Ziedrich.

By Mike Swisher

Angus MacDonald had already lived more than half of his long and remarkable life by the time I became acquainted with him. He had been born and grown up in Australia, had been ordained a clergyman, had emigrated to the United States on the first ship to carry civilian passengers to this country after World War II,

Angus MacDonald had already lived more than half of his long and remarkable life by the time I became acquainted with him. He had been born and grown up in Australia, had been ordained a clergyman, had emigrated to the United States on the first ship to carry civilian passengers to this country after World War II,